My students have more fun!

Setting Up An Electric Guitar

(Les Paul style)

PART ONE: MECHANICAL SET UP

1. File the frets

If you want a

perfect action, no fret can be sticking up less or more than

any other. I

personally have never needed to have the frets filed on an

electric guitar that I have purchased. They have all

been done very nicely at the factory.

To check the

frets, take a 4” straight edge, slide it around on the frets

and look underneath it.

See if any light shines through between the straight

edge and the frets. See

if it rocks. See

if the end of the straight edge gets stuck on a fret when

sliding. If

you see light, if it rocks, or if it gets stuck anywhere on

the neck, you have a problem.

Also, on a used guitar, check the frets for wear --

especially the first three frets. If you have grooves

but they aren't super deep, they can usually be corrected

without replacing the frets (which is expensive to do) by

having them filed.

If you need to

have the frets filed, let a trained guitar luthier do this step.

It requires special tools and knowledge. This is what the

luthier will do:

Remove the strings

Use low tack drafting tape to protect the neck and fretboard

File with a mill bastard file with the convex side down

Every stroke, file from the center to the two edges

Then round the frets with a special file

Use a tiny paint brush to clean the filings off of the neck

Remove the

drafting tape

2. Clean the guitar (used guitars only)

Remove all six strings.

Get some clean cotton rags to use for cleaning. White

flannel with no chemicals (cheap at a fabric/craft store) is

best. Or a microfiber towel. Do not use anything that has been

treated with fabric softener.

A good cleaner for urethane gloss and semigloss finish

(which on most electric guitars is everything except the

fretboard and possibly the back of the neck if the neck is

unfinished) is Rosinol lighter fluid (or naptha, which is

the main ingredient in lighter fluid). It cleans but

doesn’t damage the finish. Second choice: denatured

alcohol. (Note:

naptha is highly toxic to breathe. Use a mask and have

adequate ventilation.)

After cleaning, wax the guitar so that when you clean the

neck all the little steel wool fragments will be repelled

off the body and you won’t scratch the guitar with

them. Any high quality non-silicone car wax will work

well on an electric guitar.

I use Turtle Wax “Ice” spray-on car wax.

Another good wax is Turtle Wax Express Shine spray-on clear

car wax. Do not use a wax or polish with a heavy

silicone base. Do not ever put wax or polish on the

fretboard. Don’t forget to wax the headstock (with the

strings off). If

your guitar’s neck is either painted or gloss urethaned on

the back side, be sure to also wax the back of the neck. If the back of

the neck is raw or dull finished, it’s usually best to just

leave it, or perhaps to lightly polish it with dry 0000

("four aught") steel wool going with the grain.

While all the strings are off, tighten the tuner nuts.

Use a 10mm deep well socket. Don’t overtighten; just a

little snug down. Also

check the tension of the tuners. Turn the tiny screw

in the end of the tuner button, clockwise to increase or

counterclockwise to decrease resistance to turning, so that

they are all have the same feel when twisting.

If you have a rosewood fretboard that is very dirty, use dry

0000 steel wool to clean the fretboard. You can get this at

any hardware store. Don’t use any chemicals.

Don’t rub the steel wool sideways. Go with the

grain. When finished, sweep clean with a clean new

soft paint brush. If your rosewood fretboard is not

excessively dirty, skip the steel wool and skip to the next

step.

Apply oil to the rosewood fretboard. Boiled linseed

oil works well. I personally use Music Nomad Fretboard

F-ONE Oil Cleaner & Conditioner. It has no lemon

oil extracts, waxes, petroleum distillates, silicone, or

water. (Do not use Lemon Oil on the fretboard; lemon

oil is highly acidic and also contains d-limonene, which is

a strong solvent that is used to remove paint and

glue. Both the acid and the d-limonene will dry out

the fretboard.) Blot the oil into a paper towel.

Don’t drench the paper towel.

Just a thin coat is all you need. Rub with the

paper towel to loosen any dirt or grime. Don’t let it

soak into the fretboard. As soon as it’s been evenly

applied, then aggressively wipe off all the oil that has not

sunk into the pores with a clean cotton flannel rag.

Wipe it dry; you don't want oil touching your fingers or

your strings.

If your

fretboard is maple, there are varying opinions about care

for maple fretboards, and I have no personal experience with

them, so you’ll need to do your own research.

3. Install a new set of strings

Be sure to do the set up with a brand new set of the exact

brand and gauge of strings you will be using. For a

discussion of types of strings, LINK HERE.

Install the strings one at a time. I use a simple

method of winding strings that is recommended by Taylor

Guitars. Stretch out each string one at a time and cut

it to length with a pair of dykes. The lowest three

(thickest, wound) strings should be cut to a length about

one tuning pin past the pin it goes into (e.g., for the E

string cut it just past the A pin, A just past the D pin,

and D string just eyeball the distance where another pin

would be past the end of the headstock). The top three

(thinnest, plain steel) strings need a little longer winding

to push the string below the bottom of the tuning peg hole (the sharp

edge on the hole is where a string usually breaks).

So on these strings go about 1 1/2 pins past the pin it goes

into. This method will give about 3 windings on the

thick wound strings and more on the thin bare strings.

After cutting to length, insert each string straight through

the hole so that it sticks out a few millimeters, bend the

string with a sharp bend 90 degrees in the correct

direction, and tighten with a string winder (from the inside

out, which is the pin spinning counterclockwise on strings

4,5,6 and clockwise on strings 1,2,3) while holding the

string with tension with the thumb and forefinger of the

other hand. Make sure the winds go downward, not

upward, and that they are even and snug against each other,

and that they do not cross on top of each other. There

is no need to cross the string over itself. The shape

of the tuning pin will push each wrap against the wrap above

it, which will provide tension so the string will not slip.

NOTE: If you are using

Pyramid pure nickel strings or any other vintage style

strings with round core wires, you need to bend (crimp) the

string before you cut it, or the winding will loosen and

unravel as soon as you cut it, and you'll end up with a dead

sounding string. Crimping the strings is easy to

do. On the bottom three (wound) strings, simply

measure where you want the cut, mark it with a Sharpie,

insert the string through the tuner peg hole to where the

mark is sticking out a few millimeters, and lightly bend the

string around the peg. Then pull it out and with some

pliers make the bend into a 90 degree sharp bend to "set the

wrap." Then insert it through the hole again, and

tighten it up all they way to the correct pitch. THEN

cut the excess string off. The crimp and also the

pressure on the strings on the peg when tuned to pitch

prevent the string from unraveling. You don't need to

worry about this with normal, modern style strings with hex

cores, because they are wound so tightly around the sharp

edges of the hex core wire that you can just cut them and

they won't unravel.

Some people

recommend the twist-under wrap method of winding strings

onto the tuner pegs:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6klYBJCjWI&list=FLPkOKSjS1T0WGb8qBU8dWUw&index=55&feature=plpp_video

I have used the twist-under wrap method in the past, but

have found that the simple method described above holds the

strings just fine and the guitar stays in tune just as

well. The simple method is faster to install the

strings and also easier to remove the strings when it’s time

to change them, and it gives a cleaner, better looking wind.

After installing each string and partially tightening it,

stretch the string. Start at the bridge. Lift the string

with one hand. Use the other hand to stretch ¼th of the string at a time. Then

move to the next ¼th,

and so on. If you do this, it will stay in tune much

better and not keep going flat during the first few days

(making it “stage ready”).

General Information about Action:

Three things determine the height of the action (the

distance form the string to the fret): bridge height, nut

slot depth, and truss rod tension (which adjusts

the concave shape of the neck, called "neck relief"). These three

things work together, and a change in one will often require

a compensating change in another. In general, the

lower the action, the easier the guitar is to play, but if

it’s too low the strings will buzz.

Action is a compromise, based on personal

preference. Are

you willing to trade a lower action height for a little fret

buzz, or are you willing to trade no buzz for a higher action? What is your

playing style? If

you’re a rocker, you’ll need a higher action, because

strumming hard makes for more buzzing. With jazz, you

can get away with a lower action. In

general, you adjust the truss rod, then tweak the bridge, then

file the nut and the nut slots, then adjust the rod again,

then tweak the bridge again, and so on, until the action is

the lowest it can be with no more buzz than you’re willing to

live with. There

is no right or wrong. If

you feel comfortable with the buzz you have and with the

action you have, then that’s fine!

As previously mentioned, before adjusting

the action, be sure to put a new set of the strings you’re

actually going to use. Different

gauges and brands of strings have

different tension, which will pull the neck more or less and

thus change the action.

Different brands and types of strings even in the

same gauge vibrate differently and may buzz more or less

than others because the vibration width may be wider or

narrower.

4. Truss Rod (neck relief):

The truss rod

is a long bolt that sits in a hollowed out slot in the neck,

which goes from one end of the neck to the other. The

purpose of the truss rod is to offset the tension of the

strings that tries to pull the neck upward. Without a

truss rod, the neck would bow into a concave shape.

The truss rod pulls the neck downward, thus offsetting the

string tension and returning the neck to a more neutral

shape. Not all the way straight, but most

of the way. There has to be a slight concave

curve. If

the neck is perfectly straight, the strings will

buzz like crazy. Because of

their shorter scale, Les Paul style guitars need a

little more "relief" (curve) than do Fender style

electric guitars. Different string

gauges, string alloys, and string winding methods result in

different amounts of string tension on the neck.

Additionally, age, humidity, and temperature changes affect

the wood in the neck. All these things necessitate

occasional adjusting of the truss rod to return the neck to

the "ideal" shape.

In theory, the truss rod has nothing to do with the

"action." In practice, that's not true. In fact,

the truss rod does affect the height of the action, mostly

on the frets in the middle of the fretboard. The tighter the truss rod is, the closer the

strings are to the frets, the lower the action is and

the easier the guitar will be to play, but if it is too

low the strings will buzz when you are playing on the

low frets. However, it's generally better to just

adjust the truss rod to a specific relief and then

adjust the action with the nut slot depths and the

bridge height adjustments.

To measure your guitar's current neck

relief, place a capo behind the 1st fret, and press down

with your right thumb on the 6th string (low E) between frets 13 and 14, so so

that the string is touching the first and 13th

frets. Use a feeler gauge (available at any

automobile parts store) to measure the distance between

the 6th

string and

the 6th fret. Try various thicknesses

of the gauge, sliding one at a time between the string and

the 8th fret until you find

the one that fits perfectly with no play and without

raising the string.

The thickness of that gauge is the measurement.

Then check the

same measurement on the 1st string (high E). The measurement

for the two strings should be close to equal. Based on my own

experience, and my personal preference for a low action, I

have found that if the saddle height is as low as possible,

and the frets are equal height, and the neck is straight,

then the distance between the string and the 6th fret should be appx. .015” on an

L.P. style electric guitar. This is how much the neck is bowed

inward at the center of the neck. .015” will

yield a nice low action with only a little string buzz.

(With a low action, some buzz is normal. All Les Paul style

guitars buzz a little. In my opinion, if it’s not coming through the

amp, it is nothing to worry about.)

To adjust the neck relief, first locate and expose the truss

rod bolt head. On some older Fender style guitars it's

hidden and hard to reach, but fortunately on most L.P. style

guitars it's easy to access, usually under a small plate in

the headstock just above the nut. Remove the two or

three tiny Phillips screws, remove the plate, and you'll see

the Allen style head of the rod. Your guitar should

have come with an Allen wrench that fits it. If not,

find one, and keep it in your guitar case, along with a

small Phillips screwdriver.

if the

measurement is larger than you want, turn the truss rod bolt

clockwise to tighten the rod, which will lower the strings

and decrease the neck relief. Or if the measurement is

smaller than you want, turn the truss rod bolt

counterclockwise to loosen the rod, which will raise the

strings and increase neck relief. It is recommended to

loosen the strings slightly before adjusting the truss rod

to reduce the pressure on the threads so you don’t strip the

threads. I personally prefer to hold the guitar

against my chest and simply bend the neck back while turning

the wrench to relieve pressure on the threads while turning

the wrench in either direction.

Adjust the rod 1/6 of a turn at a time (one face of the

Allen head) then tune the guitar, check the measurement, and

check the action for buzzing. Then check again after

10 minutes to let the wood settle to the new tension (wood

is slower to settle in than steel). You can speed up

this process by putting one hand on the headstock and the

other hand on the body and pushing the neck in the direction

you’re trying to make it go (backward if tightening the rod

and lowering the action, forward if loosening the rod and

raising the action).

5. Bridge Height:

The height of

the bridge determines the height of the action (distance

from the string to the frets) on high frets (from the middle

of the neck to the end closest to the pickups). Like

with the truss rod, the smaller that distance, the lower the

action is and the easier the guitar will be to play, but if

it is too low the strings will buzz when you are playing on

the high frets. To measure the bridge height, place

the guitar on its back with no weight on the

neck. Measure the string to fret gap at the 12th fret with feeler gauges.

Various web sites suggest various action

heights. One

suggests a low action would have .078” on string 6 (low E) and

.063” on string 1 (high E) at the 12th fret, while .125” on string 6 and .094” on string

1 would be considered a high action. (Typically, you

can have the high E around .015” to .030” smaller gap/lower

than the low E.)

Personally, I prefer to go a tiny bit lower

than their suggestion for low action. My action as

measured by open string height at fret 12 is .075 on string 6 and .060

on string 1, and I love it!

On an L.P. style guitar, bridge height is

adjusted by turning the two screws that mount the bridge to

the body. Clockwise

to lower the bridge and reduce the string height at fret 12,

counterclockwise to raise it. On some other electric

guitars, and some aftermarket bridges, the height of each

string can be adjusted independently.

6. Nut slot depth:

Nut height and

nut slot depth affects string height at the end of the neck

closest to the headstock, for open strings that are not

being fretted with your fingers. The objective is to

get as low as you can without the strings buzzing when they

are played hard, when “open” (with no fretting). This

is a tricky and somewhat time-consuming process.

Measure the

distance from the string to fret 1 with a feeler gauge. Based on a

lot of experimentation, and my own personal preference for a

very low action, the lowest you can go on an L.P. style guitar

is:

1E

2B

3G

4D

5A

6E

.010

.011

.012

.014

.016

.018

This provides little margin for error. Any lower and the

strings will buzz. A

(barely) safe margin would be .002 more than those numbers:

1E

2B

3G

4D

5A

6E

.012

.013

.014

.016

.018

.020

This is where my own L.P. style guitar is

right now; it plays like butter and, with the strings I’m

using (Pyramid 10-48 round core pure nickel), there is no

buzzing.

This is MUCH lower than the way most

inexpensive L.P. style guitars (and also most Gibson Les

Pauls) come from the factory.

For example, when I purchased my newest guitar, after

adjusting the truss rod and bridge, I measured the open string

clearance at the first fret, and this is what I found:

1E

2B

3G

4D

5A

6E

.020

.023

.032

.023

.024

.023

Wow.

That was ridiculously high! I started by filing down the bottom of

the nut, very carefully, very slowly, with many test

measurements, to get the two outside strings to my goal. To do this, I

loosened all six strings about 2 ½ turns, pulled them off the

nut, removed the nut from the guitar (this can be tricky the

first time; there are YouTube videos out there showing how to

do it). Then I

used 60 grit sandpaper on a flat surface and rubbed the nut on

it. (I like 3M sander sheets; they are fantastic!). I used an ultra

fine Sharpie to make a mark for how much I calculated I should

sand off. I

never went more than half way on that mark before reinstalling

the nut and tightening the strings and remeasuring. I did this over and

over and over again. It

took hours, but the result was worth it. Remember, if you go too low, you have to start all

over again from scratch with a brand new nut.

Another thing to watch out for: On one

guitar, I sanded down a nut to perfection (or so I thought). The next day, the

guitar was buzzing like crazy.

I remeasured, and guess what? The nut had settled into the neck

overnight and all my strings were .005” lower than they had

been the previous day. So

when you are getting close, make sure the nut is seated and

smashed down with the strings fully tuned and let it sit a few

minutes to settle, then play the guitar a few minutes, then

measure again, before deciding to sand any farther!

After going through this process on my

newest guitar, this is what I ended up with:

1E

2B

3G

4D

5A

6E

.012

.019

.026

.020

.021

.020

As you can see, both of the outside strings

were exactly where I wanted them. I then needed to hand file string slots

2-5, one at a time, very slowly and carefully, with many test

measurements, to get all six slots to my goal:

1E

2B

3G

4D

5A

6E

.012

.013

.014

.016

.018

.020

To do this, you need to have a set of files

that are the same widths as the gauge of the strings. These special nut

files are fairly expensive, but they are worth it. The

best place to buy them is StewMac.com.

If you can't afford them, try to borrow some. If that

doesn't work, the cheap man's solution is to go to the auto

parts store and buy a feeler gauge tool, then with a

Dremmel tool with a thin cut off wheel on it carve teeth into

all the measuring spades.

In essence, turn the feeler gauge set into a set of

files of various widths.

I’m not sure if I recommend this, but back in the day I

set up quite a few guitars using that tool.

There is another, easier, faster way to

measure nut height: Place a capo between the 2nd fret and the 3rd fret and measure the clearance between the bottom

of the string and the 1st

fret. There

should be some space at 1st

fret. If there

is no clearance, there will be buzzing. How much

clearance? One

web site says .010”, but I find that I can get away with

.005" or even less on the first couple of strings, working

my way across gradually increasing the clearance to about

.010" on string 6.

After your nut slot depth is finalized,

check to make sure that the three wound strings (4G, 5A and

6E) have 1/3 of the string exposed, raised above the nut. If one is not

exposed enough, file the top surface of the nut to expose more

of the string.

After finalizing the nut height and the nut

slot depth, play the guitar and see how it feels and how much

it buzzes. Then

go back and tweak the truss rod and bridge height. Experiment until

you get the action just the way you like it.

If any of this sounds too difficult for

you, I recommend that you have a guitar luthier do it for you.

7. Intonation:

After the nut height, nut slot depth, truss

rod, and bridge height are set up, tune the strings perfectly,

then test the octave of each string to see if it is in tune

(finger the 12th fret). If

the octave is sharp, you need to make the string

longer. If it is flat, you need to make the string

shorter.

On L.P. style guitars, the bridge has a separate "saddle" for

each string. The saddle is the highest part of the

bridge where the string touches. Each of those six

saddles is individually adjustable to slide back and forth, in

order for each string to be lengthened or shortened. Under each string, in the

side of the bridge facing the pickup, there is a little

screw (usually flat blade). If the octave is flat, you

need to make the string shorter by twisting the screw

counterclockwise to move the saddle forward towards the neck. If the octave is sharp, you need

to make the string longer by twisting the screw clockwise to

move the saddle towards the tailpiece. (When going

counterclockwise, push on the head of the screw while you

twist, to make sure the saddle is moving and the screw is

not just loosening.) Twist a few turns, re-tune the

string, and test the octave again. With trial and

error, you'll find the perfect spot where the open note and

the fretted octave are equally in tune on your tuner

display.

8. Tailpiece:

Joe Bonomassa claims it gives the Les Paul

more sustain if you bolt the tail piece all the way down and

top wrap the strings around it. Supposedly the benefit

comes from increased vibration transfer to the body resulting

from bolting the tail piece solidly down onto the body. Other people online

claim that either top wrapping or simply raising the tailpiece

to reduce the angle of the string bend over the bridge allows

the strings to ring a little more, which adds some extra

harmonics.

On the other hand, most Les Paul setup

instructions say to do the opposite. They say for maximum sustain to lower

the tail piece as far as possible without the string touching

the bridge: “The tailpiece should just be lowered enough so

that the bass strings just do not touch the bridge for maximum

sustain. The

tailpiece can be offset a little higher on the bass side.”

The best expert I know told me that top

wrapping or raising the tailpiece will only improve the sound

if you are using heavy gauge strings like Joe Bonomassa uses

(which are hard to bend and stiff to play). If you top wrap or

raise the tailpiece with light gauge strings, there is not

enough bend in the strings at the bridge to put enough

pressure on the bridge to transfer the tone to the body. With normal and

thin gauge strings, the opposite of what Bonomassa says is

true: a steep angle helps.

The height of the tailpiece is adjusted with the two giant

flatblade screws in the end of the tailpiece. Clockwise

lowers it; counterclockwise raises it.

I personally have my strings go straight into the tailpiece,

and I have the tailpiece all the way down as far as it will

go.

9. Speed Knobs:

With pull pots (discussed below), the stock

Gibson "hat" knobs (AKA "bell" knobs) are too hard to grab and

pull quickly during performance, especially when holding a

pick. If you are

using pull switch pots, the cheapest and best modification

ever is to buy some “speed knobs” (also called "hatbox" or

"barrel" knobs) which are much easier to grab and pull. Even if you are not

using pull switch pots, speed knobs are easier to grab and

turn, and most people also think they are better

looking. Many colors are available on Amazon and Ebay,

but be careful: not all speed knobs will fit your

guitar. There are two different sizes of pot shafts on

L.P. guitars:

The "USA" or "Imperial" or "SAE" or "fine" or "24 spline" type

is 3/8". The shaft has 10 splines on each side of the

split shaft for a total of 20. The knob has 24 splines

because it has 4 more ridges to account for the space in the

split. This type is stock on USA made Gibson Les Pauls.

The "metric" or "coarse" or "18 spline" is 6mm. The

shaft has 8 splines on each side of the split shaft for a

total of 16. The knob has 18 splines because it has 2

more ridges to account for the space in the split. This

type is stock on most L.P. style guitars made in Japan, Korea,

and China.

Do not get the wrong knobs

for your pots; they will not fit!

10. To Prevent Switch, Knobs, and Jack

from Loosening:

Loosen the

pickup selector switch nut, the output jack nut, and the four

pots’ nuts. Paint the threads with clear fingernail polish and

reassemble. This

will prevent them from coming loose.

PART

TWO: ELECTRONIC SET UP

11. Audio vs Linear Taper Pots:

Most Les Paul style guitars come with

linear taper pots (look on the back of the pot to see which

type you have: "A" means “audio” and "B" means linear; for

example B500K means linear taper, 500,000 ohms).

Most people who try audio taper pots prefer

them, but only if they are a good brand. If not, they are

lousy. You have

to spend more for a good quality true audio taper pot. Bourns and PEC make

good ones. Alternatively,

you

can modify a linear taper pot with a feedback resistor to give

you a reasonable approximation of an audio taper response.

Here is a great article on this topic: http://www.geofex.com/article_folders/potsecrets/potscret.htm

Personally, I don't want to mess with it so I just buy

quality Bourns audio taper pots. They work great.

What is the difference between linear and

audio taper? A

linear taper pot rolls off the actual volts (and therefore,

the actual volume) evenly.

As you turn the knob down, the drop off of actual

volume is smooth. However,

human beings don't hear changes in volume evenly. As volume

increases, we notice increases and decreases less and less. Some experts say it

takes as much as 10 times as much actual volume for us to

perceive a doubling of volume. Thus, although linear taper

pots roll off actual voltage and actual volume smoothly, they

seem to roll off the

volume very slowly at the beginning, and then faster as it

goes. The change

at the beginning (10 to 7 on the knob) sounds very slow and

barely noticeable. Then

as we turn the knob down more, we perceive the volume dropping

very rapidly at the end (3 to 0).

In contrast, with audio taper pots, the

actual voltage and volume drop in a logarithmic manner: very

rapidly at the beginning (10 to 7) and then very slowly at the

end (3 to 0), but the roll off seems smooth to our

ears, with a perceived drop that is equal at the beginning (10

to 7), in the middle (6 to 4), and at the end (3 to 0).

On a clean sound, the purpose of the volume

pot is to actually control volume, and audio taper works well

for this because it gives smooth control of perceived volume. But on a distorted

amp, turning down the volume doesn’t really decrease the

actual volume coming out of the amp very much. Mostly, it reduces

distortion and cleans up the sound. This is where opinions vary. Some people say

dialing back distortion in the amp is smoother with a linear

pot because an audio taper drops the output too rapidly at the

beginning of the turn to get a smooth transition, whereas the

linear dials back volume more slowly/smoothly at the beginning

of the turn, providing fine “shades of dirt.” Critics of this idea

(including me) say that with linear taper most of the

“cleaning up” happens below 3, and it is very sensitive in

that range and, therefore, hard to control.

In contrast, with audio taper, the

“cleaning up” happens quickly and linearly. Some people

(including me) like this because they want a fast response to

pull back distortion and don’t want to turn the knob so far to

get the reduction of distortion. One guy said, “I find audio taper easier

to use in a gigging situation because most of the change is at

the useful end of the volume pot, so smaller adjustments are

required. I find

cleaning up by going from 10 to 5 a lot easier than cleaning

up by going from 10 to 2, which can be hard to find in a split

second in the middle of a song when you're not actually

looking at the guitar - you have to go to 0 then roll it back

up!” A friend of

mine who uses audio taper likes to set his amp to feedback at

10, screaming solo at 9, and when he dials volume to 5 he gets

a clean sound.

I strongly prefer audio taper volume pots. They seem much more usable, logical, and musical to me than linear. After doing some research, I concluded that Bourns “premium” audio taper pots are the very best on the market. These pots use a conductive polymer resistor, instead of carbon, that is accurate and very quiet, and doesn't wear out like carbon does. They make two types: the black 95 “Premium” pot and the blue 82 “Vintage” pot. The 82 is a little bigger and costs a little more than the 95, but lasts longer and has easier solder tabs, and that's the one I use for my volume knobs. They are expensive but they work really well, are completely silent, and should last a lifetime.

The only bad thing about the 95 and 82

premium pots is that Bourns does not offer them with DPDT

switches, which are needed for various modifications that are

discussed below. Bourns

does make some reasonably priced audio taper pots that use

carbon media that have DPDT push-pull switches. They are

not as good as the premium pots, but they are decent

quality. That's what I use for my tone

knobs.

One more thing to be aware of when buying

pots is the length of the shaft. Guitar pots are offered in two shaft

lengths: “short shaft” (the threads are appx. 3/8”) or “long

shaft” (the threads are appx. 3/4”). Not all L.P. style guitars use the same

length pots. Before buying pots, make sure you know

which length your guitar uses.

When replacing pots, be sure to solder the ground wires

correctly. Any "cold solder joints" will cause noise, or

damage tone, or come loose. I highly recommend the use

of a 50W soldering iron and some rosin flux. A 30W iron

can't heat the back of the pot hot enough to bond it to the

solder; and even if it could, it would take so long to heat

the joint that it could damage the pot.

12. True Bypass Tone Pots:

To get a tiny bit more brightness when the

tone knob is all the way up, you can modify your tone pots so

that when turned up all the way (10 position) the signal is

completely disconnected from the capacitor (true bypass). This is done by

removing the back of the pot and using an Xacto knife to

scratch/scrape off the carbon on the pot at the full volume

position. This

is nice in theory, but there’s a problem: to do this, you have

to disassemble the pot… and you can’t disassemble Bourns

premium pots (they are sealed), nor a push-pull pot with a

DPDT switch mounted on the back. Besides, the difference

would be so small as to hardly be worth the effort.

13. Modified Treble Roll-Off Tone

Capacitor:

The capacitor in the stock tone circuit is

a high pass filter. That

means only the high frequencies pass through, and the bass

frequencies are cut off.

But because the capacitor is wired to ground, the

effect is opposite: it acts

as a low pass filter in the signal path because it

bleeds off the treble to ground. Thus, the high frequencies are dumped to

ground, while whatever tones remain (low frequencies) continue

on to through the volume control and out the jack to the amp.

This is why the circuit is called a low pass filter,

because the lows "pass" through the circuit while the highs

are eliminated.

The value of the capacitor (mF or uF)

determines at what point in the frequency spectrum the

frequency cut-off occurs.

The higher the capacitor value, the lower the frequency

of the cut-off point. In other words, higher capacitance value

caps will make your tone darker when the tone control is set

below 10, because in addition to very high treble frequencies,

some upper midrange frequencies will also be dumped to ground

as the tone knob is turned down. Les Pauls generally have .047 uF caps,

although most L.P. clones use .022 uF. Various people use

caps as high as .068 uF and as low as .010 uF. Personally, I

prefer the .022uF.

The amount of reduction of treble tones

above that frequency is determined by the value and position

of the pot (and this, of course is affected by whether the pot

is audio or linear taper, as discussed above).

The bottom line is this: If you don’t like

how your guitar sounds when turning down the tone knob because

too much upper midrange is being cut, so it sounds muddy and

lacking definition, and you find yourself wishing the tone

knob would only attenuate the very highest treble frequencies

instead, you can choose a smaller capacitance value capacitor. This will make the

elbow of the curve a higher frequency, so that turning down

the tone knob does not make the sound as muddy. Conversely, bigger

capacitance value capacitors will roll off more upper midrange

tones.

In addition to reducing treble as the tone

knob is turned down, the capacitor also has another function

in the circuit. When

the tone knob is turned all the way up (to 10), the capacitor

acts as an inductor that improves the tone of the guitar. Gibson’s web site

explains it this way: “When rolling a tone control all the way

back, the capacitor forms a resonant circuit with the pickup

that provides a midrange boost.” The reason guitar experts use big, fat,

high voltage capacitors instead of smaller ones is increased

inductance. A

.022 uF 400V capacitor sounds better than a .022 uF 25V

capacitor even though they have the same capacitance value

(and even though guitar circuit voltages are measured in

millivolts).

Different brands and types of capacitors

make the tone circuit sound different, even if they are the

same capacitance value and voltage rating. Cheap ones can be

very inaccurate and can vary in capacitance +or– 20% from

their stated value. Also,

with cheap capacitors, capacitance can vary with frequency,

temperature, and applied voltage. Some cheap capacitors are even

microphonic, which means they make noise when the guitar is

moved. If the

capacitor value is inconsistent, the resonant peak created by

the capacitor can have a different frequency at different

times. All this

can make the guitar sound different under different

conditions. All

L.P. knock offs, including Epiphones, and even most Gibsons,

come with cheap capacitors.

Sprague Orange Drops are generally

considered a very good upgrade capacitor for the price. They offer

stability, resistance to temperature variation, low moisture

absorption, excellent characteristics in AC circuits, no

microphonics, and therefore consistent tone. The Orange Drop

“715” (600V) is the current production capacitor that is

recommended by most people.

The Orange Drop “716” (400V) has more flexible copper

leads and costs more but some people say it doesn’t sound as

good because it is compressed during manufacturing so that it

is not round in shape. I

found a pair of NOS Orange Drop 418’s (600V .022uf) on Ebay

for super cheap. Some

people say they sound even better than the 715’s. All I know is they

sound great in my guitar.

Replacing capacitors is an easy soldering job. Just

remove the existing caps and solder the new ones in their

place.

14. Capacitor Markings:

Modern Orange Drop and other newer

capacitors are not intuitive to read the value. Instead of

traditional uF markings, the value is stated as a 3 digit

number: 2 digits, followed by another digit that indicates how

many zeros to add on to get picofarads, followed by a letter

that indicates tolerance.

micro is uF = .000001F (1 millionth of a

farad)

nano is nF = .000000001F (1 billionth of a

farad)

pico is pF = .000000000001F (1 trillionth

of a farad)

Examples:

102J means 1,000 pF which is 1 nF which is

.001 uF

682J means 6,800 pF which is 6.8 nF which

is .0068 uF

123J means 12,000 pF which is 12 nF which

is .012 uF

473J means 47,000 pF which is 47 nF which

is .047 uF

(J is + or – 5%)

15. Treble Bleed (aka Treble

Compensation or High Pass Filter):

With “modern wiring” (with which nearly all

Les Pauls and L.P. clones have come from the factory since the

mid 1960s), as you turn down the volume, the treble decreases,

making the tone darker. I’m

not completely clear on the reason why. All I know is when

you turn down the volume (even just a bit), the high end or

treble loss is not proportional to mid and bass reduction. A small cut in

volume creates a far greater reduction of treble than of bass.

One way to deal with this annoying treble

loss is to install a “Treble bleed” capacitor onto the tone

knob pot. The Treble Bleed cap goes across the

terminals of the volume pot.

It acts as a high pass filter that allows treble

to bleed across the volume pot and not get turned down as much

when the volume is turned down.

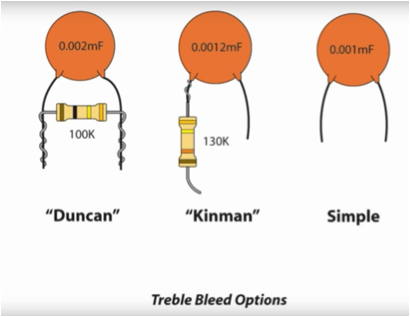

There are three types:

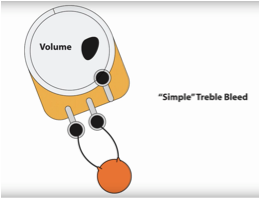

“Simple” (right above

and right below) is simply a high pass filter. It seems stupid

to me because it allows the full treble to always go to

signal path no matter where the volume knob is. In other words,

the volume knob won’t turn down the volume of the high

frequencies at all.

(Including if the volume is turned all the way down!) Another problem

is selecting a value for the capacitor. Premier Guitar

recommends a 300-500pF capacitor (silver mica), while the

diagram above recommends .002mF, which is 4-5 times as

big. So, who

is right?

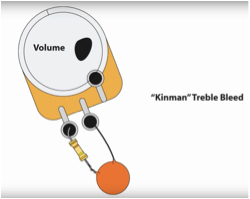

“Kinman” (center in both of the above

diagrams) does the same thing as Simple, but the

addition of the resistor makes the effect less drastic. This one

makes more sense to me.

But again, opinions on what size of capacitor and

resistor to use vary widely. The diagram above recommends a

.0012uF with a 130K resistor. Premier Guitar also recommends a

.0012uF silver mica capacitor and a 130K resistor. But someone

else online said “2A123J (.012 uF, which is 10 times as

big!) cheap green capacitors work, and you can try any

resistor you want.”

Again, who to believe?

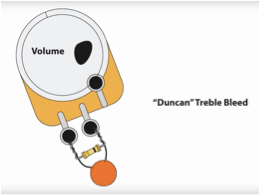

“Duncan” (left in both of the above

diagrams) is also less drastic than a Simple, but it

additionally modifies the effectiveness of the pot in

turning down the mid and bass frequencies. DiMarzio

recommends the Duncan style with a 560pF capacitor and

a 300K resistor. However,

the above diagram recommends a .002uF capacitor (4 times

as big) and a 100K resistor (3 times as low). Premier Guitar

recommends halfway inbetween: a .001uF capacitor and a

150K resistor.

Once again, it is hard to know who to trust.

All of these options are very easy to

install. Just solder the capacitor (and resistor)

to the terminals of the volume pot as shown in the

diagrams. But all of them seem to have problems

from a common sense standpoint. It seems to

me that they have the potential to create the opposite

problem: as you turn down the volume, the treble

increases and the tone becomes brighter!

A fourth option is proposed online by

someone named Frank Falbo. It seems to make the most logical

sense to me. He

doesn’t like the three common Treble Bleed circuits

because he claims they don’t work for clean jazzy solo

stuff with the tone control down. He says, “The

problem is when you've got the tone knob down, and

you're working the volume knob, at the tone knob you're

cutting the highs, while on the volume side you're

letting the highs pass through while reducing the lows,

so you're sucking tone from both ends.” His solution is

instead of the high pass cap jumping across the volume

pot, the high pass cap runs through the tone pot (see

diagram below). This

makes the tone pot into a double purpose pot. One side of

the wiper still controls the amount of treble cut from

the tone knob, while the other side controls the amount

of treble added through the Treble Bleed cap. When you have

the tone knob all the way up, there is no change. The pickup

hot is feeding 100% through the Hi-Pass cap to the

center lug, and everything is as it was. But as you turn

the tone pot down, the Hi-Pass cap becomes less and less

"connected" to the pickup hot (due to the tone pot's

resistance increasing) and therefore allows less and

less "Hi-Pass" filtering to occur. Eventually, when the

tone knob is all the way down, the Hi-Pass is

disengaged. This

makes the tone knob totally usable even when you're also

playing with the volume knob.

Some people claim that a

treble bleed circuit is the worst thing in the world

and that it will destroy the tone of good pickups. Pickup

manufacturers say this is a massive over-statement,

and that most people who try treble bleed circuits

with correct sized capacitors and resistors find them

to be a good improvement with little or no perceptible

tonal trade-off.

Personally, I decided to not do any

of these high pass treble filter options, because I am

more impressed with the other option for fixing the

treble drop problem: Vintage Wiring (below).

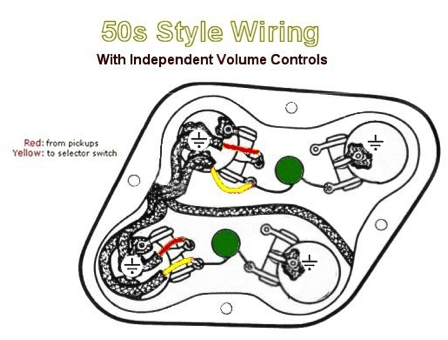

16. Vintage Wiring:

“Vintage wiring” is another way to get rid

of the treble loss when turning down the volume pot.

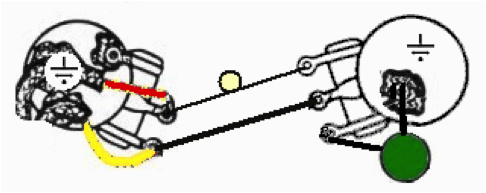

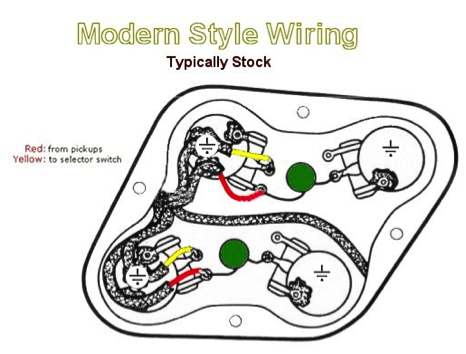

With “modern wiring”

(see below), the tone control receives its signal from

the input of

the volume pot. Thus,

it is connected directly to the pickup. The advantage of

modern wiring is that the overall volume does not drop

when you turn down the tone knob. The disadvantage

is that it results in the nonproportional treble

attenuation when turning down the volume knob discussed

in the previous section.

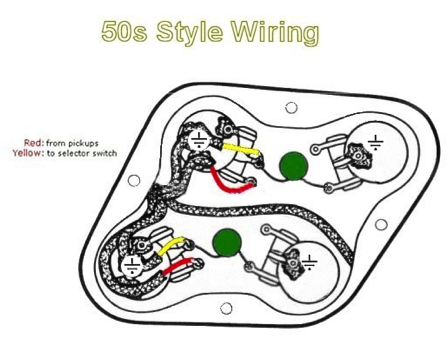

With “vintage

wiring” (see below), which was used in Les Paul’s in

the 1950s and early 1960s, the tone control receives

its signal from the output of the

volume control (i.e., the wiper of the volume pot… unless you

use volume knob isolation, discussed below). In this

method, the voltage going to the tone circuit is

always equal to the voltage going to output, no matter

how the volume knob is set. This makes the effect of the

tone circuit proportional to the volume, regardless of

where the volume knob is. The advantage is

that turning down the volume does not increase the

percentage of the treble signal that goes to the tone

cap and pot, and therefore, when you roll down the

volume control, you don’t have a disproportionate

treble roll-off. The disadvantage is that

turning down the tone knob decreases the overall

volume a bit.

I have a friend who owns a 1964

Gibson SG, and it came from the factory with vintage

wiring. He likes it so well that he has

re-wired all his guitars this way. It

eliminates the treble loss without the need for a

treble bleed (discussed above.)

Which is better? It really

depends on your guitar, pickups and playing style. The

modern wiring will maintain the overall volume

better when you roll down the tone knob, but at the

cost of losing a bit of high end when you roll down

the volume knob.

If you have a bright pickup that may not seem

that bad of an idea, because with less volume and

the same amount of treble the tone might be too

piercing. On

the other hand, the vintage version keeps the amount

of treble the same when you turn down the volume but

drops a bit in volume as soon as you roll down the

tone pot. What

you might prefer is very much subject to personal

preferences."

This is a super easy modification to do. Just

unsolder the capacitor from the left terminal on the

pot and solder it to the center terminal.

I’m very fond of vintage wiring.

I have

modded my guitar to have vintage wiring, and it

works great.

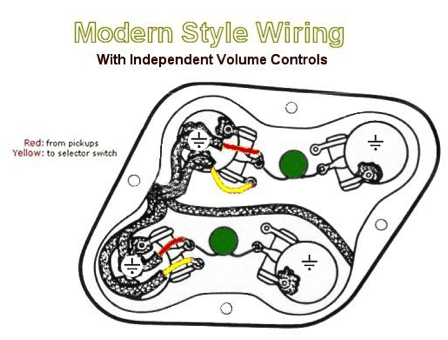

17. Isolation of Volume Pots

(AKA Independent Volume Controls):

With stock wiring (either modern

or vintage), when both pickups are engaged (i.e.

when the pickup selector switch is in the center

position), when you roll down the volume of one

pickup, even slightly, while leaving the other fully

open, this makes the latter much louder than its

mate. Even worse, backing down just one of the

volumes to zero shuts off the entire guitar. This

happens because the pickups are wired in parallel to

each other so the two volume controls interact, so

that if you roll off the volume of either pickup, it

affects both pickups rather than just the one you

turned down. This

is very annoying.

It eliminates part of the advantage of having

separate volume controls for each pickup (in fact,

with the switch in the center position, you would

have better control with just one master volume

circuit.)

There is a

simple modification that cures this. On each

volume knob, instead of wiring the middle (wiper)

lug to the output and the left outside lug to the

pickup, you can wire the middle (wiper) lug of the

volume pot to the pickup and the left outside lug to

the output. This

trading of input and output lugs will “isolate” the

two pickup circuits so that turning down one pot

won’t reduce the volume of both pickups. Here’s why

it works: With stock wiring, the more you turn down

the bridge pot, the less resistance to ground there

is going from the neck pickup through the bridge pot

to ground. But

with the isolation wiring modification, if you turn

down the bridge volume pot, there would still be

500K resistance to ground going from the neck pickup

through the bridge volume pot.

This is another

easy modification to do. Just unsolder the

wires going to the volume pot, trade them, and

resolder.

The advantage of

this modification is that in the middle

switch position you are allowed to dial in the exact

balance you want between the two pickups without

sacrificing volume. In theory, this

might sound neat, but there is a big disadvantage:

as you turn down volume (with the selector in any

position), it takes out a huge amount of your high

end. In

other words, it makes the treble bleed problem

discussed above even worse. This is

because when the volume pots are wired backwards,

when you turn down the volume it will increase the

impedance to ground.

This results in a dramatic loss of treble

when you roll back the volume.

I do find it very annoying that if you turn

down one pot all the way, it kills the volume of

both pickups, even if the other one is still turned

all the way up.

But this volume pot isolation modification

would defeat the improvement gained from vintage

wiring, and make the treble loss problem even worse. So I

don’t use this modification in my guitar.

A Note about

Humbucker Pickup Theory and Terminology:

Before we move

to the next section, we need to say a word about the

type of pickups that are on Les Paul type

guitars. Unlike Fender Strat and Tele guitars

that use single coil pickups, the LP uses two

so-called "humbucking" pickups. Each of these

pickups is comprised of two separate coils, which

are wired in series. Commonly, one of the coils will

have adjustable “screw” pole pieces (designed to

give an adjustment for string-to-string balance, as

discussed in the next section), and the other coil

will have non-adjustable “slug” pole pieces. These two

coils are connected out of phase, and are reverse

(magnetic) polarity from each other - which means

they are in phase sonically. The

reason it’s called a “hum bucker” is because

magnetic energy from the string’s vibration is

created in phase, but the out of phase wiring of the

two coils will cancel most nonmagnetic

radio-frequency noise, hum and interference.

Think of it this

way: the two coils are wired opposite each other,

and they also have their magnets placed with reverse

polarity to each other. For this reason, the two

“finish” wires both come out the same side of the

guitar as each other (one goes to signal and the

other to ground) and the two “start” wires both come

out the other side (and are wired together). Even

though this makes the two coils out of phase with

each other, it works because the reversed windings

and magnet polarity reverses this and puts them back

into phase.

Pickup

terminology is very confusing. In normal

Gibson wiring, the South/Screw coil is the coil that

the “-” (or “ground”) lead is connected to ground. The

North/Slug is the coil that the “+” (or “hot”) lead

connects to the signal path. And the

South/Screw “+” (or “hot”) lead is connected to the

North/Slug “-” (or “ground”) lead. But with

different terminology, the South/Screw is the coil

that the “Finish/Inside” lead is connected to

ground. North/Slug

is the coil that the “Finish/Inside” lead connects

to the signal path.

And the South/Screw “start/outside” lead is

connected to the North/Slug “start/outside” lead. Thus, +

and - do not translate to start and finish. In fact,

the definitions are completely different and half

the time they are reversed! I’ve

decided to ignore any diagram that uses + and - . I only

use the start & finish terminology, which seems

to be used by the more sophisticated/informed

electric guitar crowd.

18. Pickup

Height:

For hottest

output, if you press the string at the highest fret,

then measure the distance from the neck pickup at

the pole to the bottom of the string, the distance

should be 1/16”.

However, there

are several advantages of having a distance of 1/8”

to 1/4”:

1) to prevent

“magnetic dampening” which is when the magnetic

force of the pickup pole piece slows down the

vibration of the string and kills sustain and

tone... (magnetic dampening decreases and sustain

increases with the string a little further away from

the pickup).

2) to reduce

string buzz by taking some magnetic pull off of the

strings that pulls them toward the frets.

3) to adjust the

relative volume of the two pickups by raising or

lowering the hotter of the two.

4) to brighten

and sweeten the tone... (a pickup too close to the

strings will be thick and dark; moving it farther

away from the strings will brighten it up).

So, if you have a neck pickup that is too dark or too loud or both, this is the solution! Lower the pickup to thin the tone and lower the volume. Turning the pickup mount screws clockwise will raise the pickups and counterclockwise will lower them.

A variation of

this is when you lower the pickup, you can raise the

pole piece screws about 1/8” to 3/8” out of the top

of the bobbin.

This makes the screw coil “hotter” (louder)

than the slug coil, which has two benefits: first,

it makes the output of the pickup stronger when

using coil cut (explained two sections below), so

that it’s not as big of a drop in volume when

switching to coil cut; and second, many people say

that unbalanced coils make a humbucker sound more

open and sweeter.

Another way to accomplish the same thing is

to tip the entire pickup a little. I like

the way my neck pickup sounds when tipped this way.

Final adjustment

to make each string equal in volume to the other

strings can be done by adjusting the height of each

individual pole piece screw. The poles

are like mini volume controls for each string. You can

stair step with the thinnest strings closer to the

screw and the thickest farther away. Step up

from E to A then D.

G might be a little lower again or the same

as D. B

should be the same as G, then high E should again

step up. In

general, it is not recommended to turn any of the

screws in so they are below the face, and most

people say low E should be almost flush.

Turning pole piece screws clockwise will lower them

and counterclockwise will raise them.

I have found

that with the pure nickel strings I’m using, the

three lowest strings (the wound strings) do not have

as much magnetic energy and thus are lower volume

than the three upper strings (the plain steel

strings) and so I have raised the screws more on the

lower three to offset this characteristic.

Rough adjustment

from side to side can also be done by tipping the

pickup slightly sideways, by adjusting one pickup

mount screw slightly higher than the other.

Lowering the

neck pickup helped my guitar tremendously. It made

the two pickups closer in volume to each other, and

it made the neck pickup brighter and less heavy on

bass. I also tipped the neck pickup slightly

so that the screw pole is closer to the strings than

the slug pole.

19. Coil cut

(aka: coil shunt, coil tap, coil split, single

coil switching):

Coil cut is a

method of wiring that changes a humbucker into a

single coil pickup by disconnecting one of the

coils. This

drops the volume and makes the sound “chimey,”

brighter, and less fat, like a Strat. Wiring

this modification isn't hard but takes some

dexterity. All

you need is one "push-pull" tone pot that has a DPDT

switch attached.

You easily can buy pots with switches on Ebay

or from StewMac.

The two wires from the neck pickup that are

connected to each other and not connected to

anything else (the South start and the North start

leads) get soldered to the center terminal on one

side of the switch, and ground goes to the terminal

directly below it. The two corresponding wires

from the bridge pickup get soldered to the center

terminal on the other side of the switch, and ground

goes to the terminal directly below it. When the switch

is “on,” this grounds both ends of one coil, while

leaving the other coil active, effectively making a

humbucker into a single coil pickup.

My L.P. clone

came from the factory with coil cut, using two DPDT

switches (one to do coil cut on neck and the other

to do coil cut on bridge). But it only takes one DPDT

switch to do a coil cut on both pickups. Because

I’ve never found a situation where I wanted one

pickup in single coil mode and the other in

humbucker mode at the same time, I wired both

pickups to one switch so I only have to pull one

switch to do coil cut in both pickups. This

speeds up the process on stage, and it also freed up

the other DPDT switch for another purpose, which

will be explained below.

In normal Gibson

wiring (screw coil goes to ground; see the previous

section), if the start-to-start jumper wire is

grounded by a coil cut switch, that would leave the

slug coil active.

There are two advantages of grounding the

screw coils and leaving the slug coils active during

coil cut: First, the slug coils are the two that are

closest together, which will give them more “quack”

when in the center switch position during coil

cut. Second, on the bridge pickup, the slug

coil is farther from the bridge than is the screw

coil, which gives it more output and warmth than the

screw coil in the "Treble" or bridge switch

position.

On the other

hand, there are two advantages of having the screw

coils active during coil cut. First,

during coil cut, the screw pickup, which has been

individually adjusted for string volume, is the

active one, so those adjustments will be active

during single coil operation. Second,

if we’ve made the two coils unequal by screwing out

the screws 1/8-3/8” (or tipping the coil), the screw

coil will be the louder of the two, making the

volume drop less drastic when switching to coil cut. My L.P.

clone was wired from the factory for the screw coils

to be active during coil cut and I've decided to

leave it that way, but it would be fun to try it the

other way to see how it sounds...

It would be cool to make the screw coil active on

the neck pickup and the slug coil to be active on

the bridge pickup, although I suspect there might be

an issue with the phase in the center switch

position. I'm not sure. I decided it was

too much work to find out, so I stayed with using

the screw coils.

20. Coil Cut

Pot:

Instead of or in

addition to a coil cut switch, you can put a volume

knob in series onto the coil cut ground. That way,

you can partially

dial in the second coil. I think this is a brilliant

idea. I

love it. I

would do it if I had a spare pot available. But I

don’t, and I don't want to drill more holes to add

one.

21.

Series/Parallel wiring within each pickup:

There are two

entirely different things people mean when they say

the words “series” and “parallel” pickup wiring. The first

is where each individual pickup is wired so that the

screw and slug coils are switched to be either in

series or in parallel with each other (stock is

series). The

other is where the two pickups are wired so that the

neck and bridge pickups are switched to be either in

series or in parallel with each other (stock is

parallel). The

first is discussed here; the second is discussed

Section 23, below.

Normally each of

the two coils in a single humbucker pickup are wired

in series. This

means the electrical signal goes through one coil in

one direction and then back through the other coil

in the other direction, such that the ground and out

wires are both on the same side of the pickup. You can

wire up a switch that can to change them to

parallel. Parallel

means you connect both coils together on both ends,

so that the electricity goes through both at the

same time, from one side to the other, such that the

ground wire is on one side and out is on the other. With parallel,

the sound is much brighter and thinner, sort of like

coil cut. One

advantage of parallel over coil cut is that parallel

retains some of the RF noise rejection of the

humbucker dual coil design, whereas coil cut is just

like a Fender… noisy.

Some people claim that parallel wiring can be

really good sounding, with “more twang” than coil

cut, and that Jimmy Page used it a lot. They say parallel

wiring is especially useful if you have hot pickups

because you can go from loud and fatter to quieter

and airier.

Another

disadvantage with individual pickup series/parallel

switching is that the wiring is very complicated,

and each DPDT switch can only do one pickup. So you

need two DPDT switches (one for each pickup) to do

parallel/series switching in both pickups. If you have

only two switches like I do because you’re using the

Bourns Premium audio taper pots with the conductive

polymer element for volume, then the series/parallel

switching it will take both of the tone knob

switches and you won't have any switches for any

other purpose.

I personally

like the sound of coil cut, which takes only one

switch, so I don't bother with within-pickup

parallel switching.

22. Humbucker

Treble Bypass:

I found this in

a YouTube video: In a normally wired (in series)

humbucker pickup, you can add a .005uf capacitor in

parallel with whichever coil is second in the series

(the one that goes to the volume knob, which in most

guitars is the slug coil). This would be done by

soldering one end of the capacitor to the junction

of the two coil wires that are wired together, and

the other end to the input terminal of the volume

pot.

This is a

particularly useful modification on a guitar that

has too muddy of a sound on the neck pickup. It keeps

the fat humbucker bottom end and most of the noise

rejection, but it lets some high frequencies through

to brighten up the tone. If it brightens up too much, an

inline resistor can be inserted to reduce the

effect. You

can experiment with different values of capacitors

to change the frequencies that are passed through,

and you can also experiment with various values of

resistors to change the amount of the effect. Or you

can use a volume pot to make it adjustable.

The theory of how this works is it lets the high frequencies from the first coil bypass the second coil, thus avoiding the blocking of the high frequencies from the first coil by the inductance of the second coil. But the low frequencies are not affected so they sound the same as they did before.

The guy on the video called this “the best of

both worlds” between series and parallel, and he says it

sounds good with distortion.

It seems like a great idea to me. You end up with the

tight bottom end of a humbucker with the high frequencies of

a single coil. I

haven’t done this personally because lowering and tipping

the pickup took care of the “dark neck pickup” problem to my

satisfaction.

23. Series/Parallel wiring between pickups:

The stock Les Paul wiring puts the two pickups

in parallel with each other when the pickup selector toggle

switch is in the middle position. The Jimmy Page wiring allows the

option to switch between parallel and series. Putting the two

pickups into series makes a very dark, fat sound. From what I’ve read and

heard, most people who have tried it

say that the series sound is not very useable

because it is too dull.

This mod takes one DPDT switch. Since I only have

two switches, and one is already taken for coil cut, I

decided that phase reverse is more useful than

series/parallel wiring between pickups.

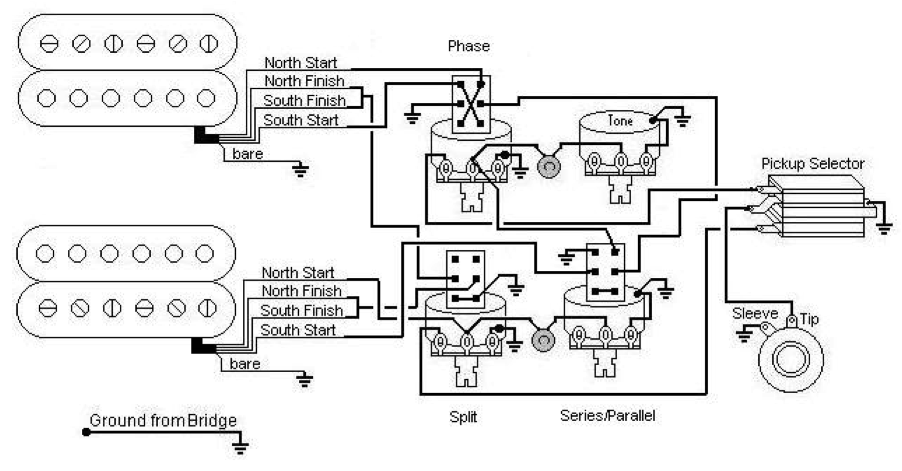

24. Phase Reverse:

This mod (also from Jimmy Page) allows you to

reverse the phase of one or the other pickup, in order to

place the two pickups out of phase with each other when the

pickup selector toggle switch is in the center position. This gives a

“scooped” sound. (The

phase reverse has no effect when the pickup selector switch

is in the Rhythm or Treble positions.)

This mod takes one DPDT switch. I have opted to

use my second switch for this purpose. I don’t use it

often, but it does make an interesting sound and I use it

once in a while.

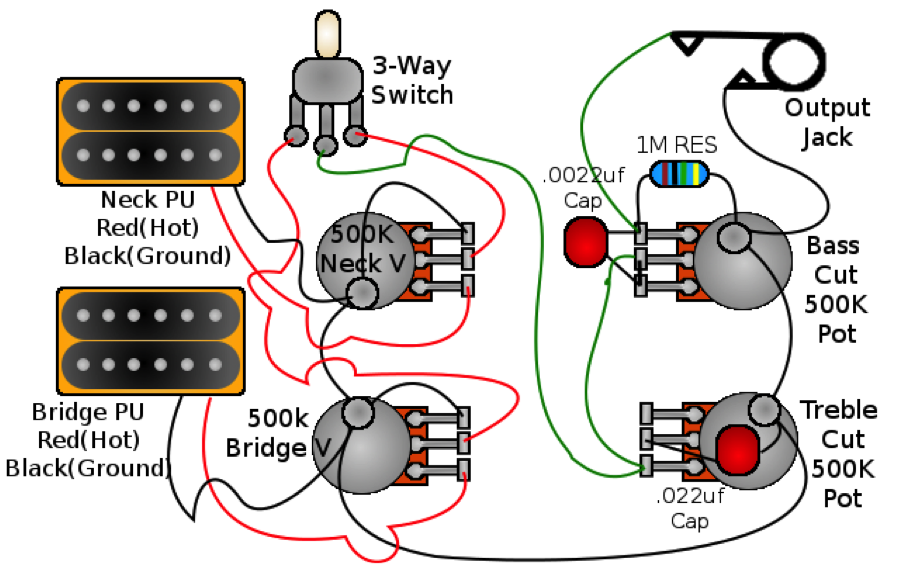

25. Master Treble and Bass Roll Off:

Below is a schematic for a master treble cut

control and a master bass cut control that use the stock

500K pots and one of the stock .022uf capacitors, plus one

.0022uf cap and a 1meg resistor. I think it’s an

intriguing idea. It

would be sort of like the treble and bass knobs on my

basses. It

doesn’t matter what pickup or pickups you’re using, there’s

one treble knob and one bass knob for the entire instrument

(instead of one treble knob for each pickup and no bass

knob). A

variation of this wiring diagram could make the treble roll

off only for the bridge pickup and the bass roll off only

for the neck pickup.

There are some obvious advantages to having a

single treble roll off and also a bass roll off. This would give

the most flexibility to instantly change tone no matter

where the pickup selector switch is and no matter where the

two volume knobs are set.

On the other hand, you might lose the inductance

effect (midrange boost) from the orange drop capacitor in

the treble roll off circuit that was discussed above. Also,

it might mess up what you can do in phase reverse mode.

Another option would be to have the stock treble

roll off on the bridge pickup and a variable Humbucker

Treble Bypass (treble add – see 24 above) on the neck

pickup.

So far, I’m happy with just lowering the

neck pickup and leaving the tone circuits stock except

to change to vintage wiring.

Overall

Wiring Summary:

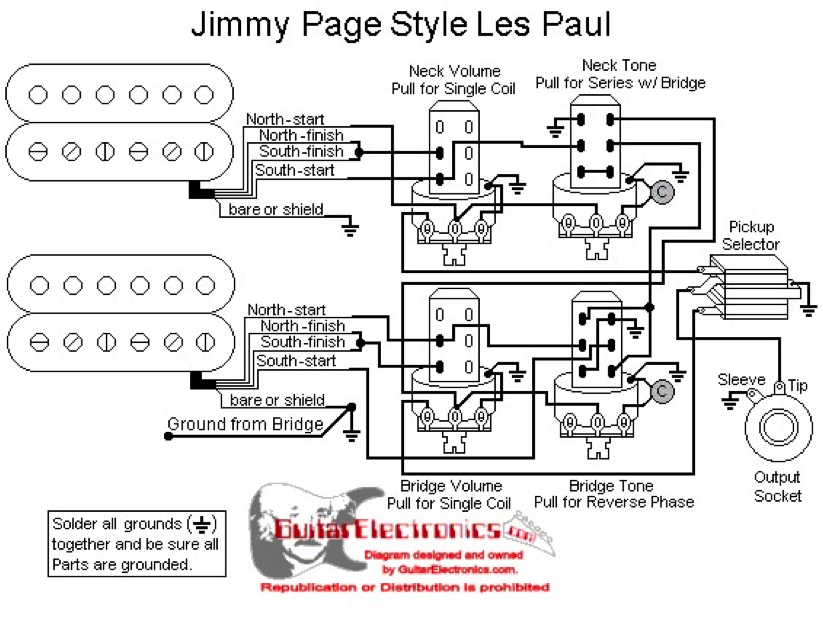

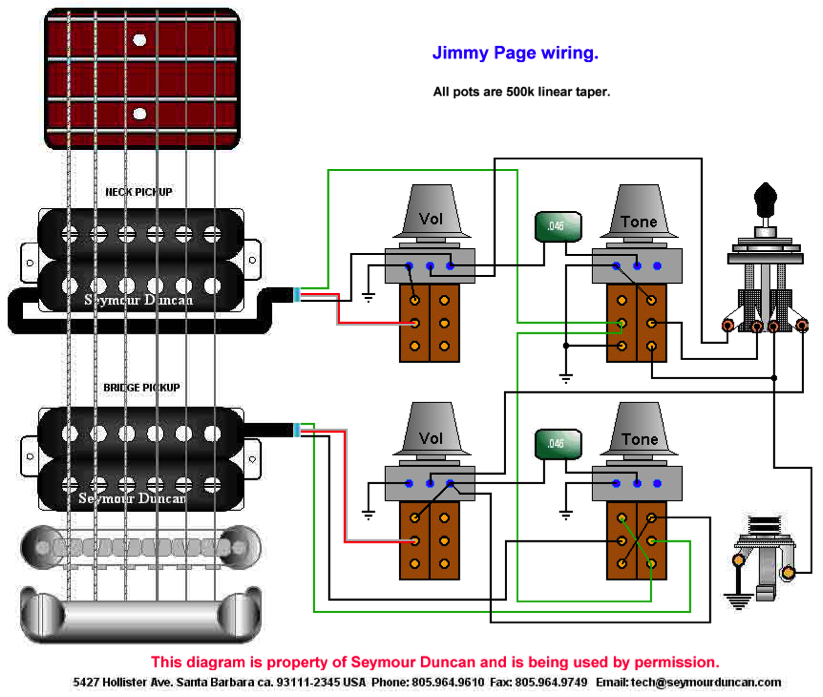

Here’s a diagram using three switches (coil

tap, phase, and parallel). I used this schematic for the coil

tap and phase, but I did not do the series/parallel:

Here’s the Jimmy page schematic

(same as above but with separate coil cut switches

for each pickup):

Recommended Maintenance Products:

Dunlop 65 String Cleaner and Conditioner on

the strings. This

stuff is great. It

cleans off gunk and strings feel silky after

application.

Music Nomad Fretboard F-ONE Oil Cleaner & Conditioner for the rosewood fretboard. It cleans and reconditions and protects.

Turtle Wax "Ice" spray-on clear car wax, or Tutle Wax "Express Shine" spray-on clear car wax, for all urethaned and painted surfaces.

CONTACT INFORMATION